Familiar, yet not so familiar

9th September 2008English may pervade all the U.K. these days, but other languages live on too and the names of places and landscape features like hills betray the influence of those non-English languages and cultures during its history. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and Norse names have remained in existence, even if they have morphed over the years. That of course, presents that challenge of pronouncing whatever a name might be and, even in England, that’s not always a straightforward matter. The usual rules do not always apply.

In Wales and Scotland, the linguistic rules of the likes of Scots Gaelic and Welsh might be very regular but you need to know them and it can be hard to discern and remember them all. Welsh is (in)famous for its additional consonants and vowel sounds, but the same comment applies very much to the Gaelic languages too. For some reason, I used to think that Irish was far more accessible to anglophones until it dawned on me what we do with vowel sounds. When you don’t know those rules, personal forenames like Aoife, Eoin, Eimear and so on become a minefield. My schooling has meant that pronouncing those names is second nature to me, so much so that I didn’t realise the traps until relatively recently.

Even I can get caught in linguistic tar pits too. The chasm that exists between Scots Gaelic and Irish is one that really comes to mind and, while visiting the Western Isles, I must admit to sticking with anglicised names like Ardvourlie and Ardhasaig in place of their Gaelic equivalents so as not to cause confusion. That isn’t to say that there aren’t similarities between the two languages; it’s just that there are enough differences to allow for woeful inaccuracy and imprecision at times from someone using his school Irish.

Take the forename Eoin, for instance. In Irish, it is pronounced like the Owen, the Welsh version apparently, while Scots pronounce it like Iain. Here’s a hill country example from Scotland: aonach. The Scots say “ann-och” while the same word in Irish is pronounced “aynock”. Not only are they spoken differently but their meanings differ too with the Scottish version meaning moor and the Irish one meaning fair or market. Gleann is yet another example of different pronunciations of the same word and with the same meaning in both languages: the Irish counterpart rhymes with clown while the Scots turn it into “glen”. It should be easy to see that the list of occasions where applying the rules of Irish to Gaelic would produce the wrong result could be a long one. It might be better to learn Gaelic without too much recourse to Irish to reduce the number of errors.

Even the English word Gaelic is uttered differently in the two countries. Scots say “gallik” after the word Gàidhlig while we in Ireland go for “gaylik” instead. Incidentally, the Irish word for the language is Gaeilge (spoken as “gyael-ge”). Both languages may have had a common ancestor but they have gone their separate ways since and I wouldn’t be surprised if Old Norse had its influence too.

Having a dictionary and following the rules that it describes would help, but there’s nothing quite like hearing a word spoken by a native speaker for fine-tuning things. Even so, I really should get out that Gaelic dictionary that I picked up in Tyndrum. It might even keep me out of trouble.

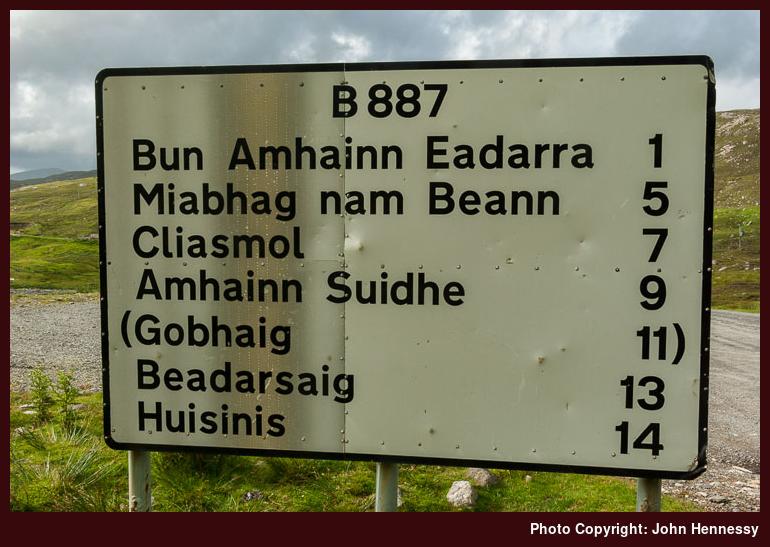

It’s my week wandering the Western Isles that has brought all of this to mind and their official title of Na hEileanan an Iar (try “na hell-a-nan an yar” if that’s new to you) should be dropping a hint as to why. Even cursory examination of OS mapping will reveal almost exclusive use of Gaelic place names and my trip reports will adopt the convention of using Gaelic names in the main with the English versions in brackets the first time that I refer to a place that has one. I won’t be distracting from the tales of my explorations with pronunciation guidance but you should be able to find anywhere that I mention on a map. Hopefully, that will make things a little easier to follow.

Please be aware that comment moderation is enabled and may delay the appearance of your contribution.